The painting "The Mill of Wijk", which was recently found and attributed to Vincent van Gogh, has been checked for its authenticity with the help of artificial intelligence and machine learning. The Munich-based AI and data science specialists at Alexander Thamm GmbH were unable to detect any anomalies that would indicate a forgery. The underlying neural network model recognises a total of seven out of eight secured Van Gogh forgeries. They were put into circulation by the art dealer Otto Wacker in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The alleged Van Gogh painting "Protestant Barn", which surfaced in Italy in 2010, is also classified as a fake by the algorithm, as by numerous experts.

The model, which has been developed and repeatedly improved by the company's Leading Data Scientist Wolfgang Reuter since the beginning of 2017, is generally able to detect forgeries with relatively high accuracy. The LKA Berlin has been supporting the project for several years - and has provided the AI expert with a total of 75 secured forgeries from six different artists during this time. On average, three quarters of the forgeries are recognised, although the precision varies from painter to painter. Of 34 Penck forgeries by the authority, for example, the model recognises 67, but of supposed Max Beckmann paintings 100 per cent. In the case of Heinrich Campendonk, the recognition rate is 90 per cent, Max Liebermann forgeries are recognised by 80 per cent.

"It is important, however," says Reuter, "that the method used always results in a certain percentage of originals being positive, i.e. classified as suspicious or conspicuous. On average, this proportion is eleven per cent. The developer therefore says quite openly that even artificial intelligence can never make a safe or court-proof judgement about whether a painting comes from a certain artist - or not. However, this also applies to all other methods of verifying authenticity.

This is how human art experts and specialists have been fooled in the past, as the case of the "century forger" Wolfgang Beltracchi, sentenced to six years in prison at the end of 2011, shows. Provenance research can also only provide clues, especially if the origin of a painting is only incompletely documented since its creation. Even chemical analyses are only of limited value, especially if the colours used are inconspicuous. After all, many forgers are meticulous about not using only pigments that were commercially available at the time a painting was supposedly created. In addition, there have been cases where newer colours were applied to a work of art via restorations. Reuter therefore sees the algorithm as a further, additional indication of authenticity that does not make any of the previously used methods superfluous, but complements them.

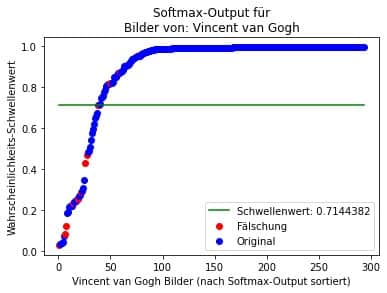

In the case of van Gogh, the precision in detecting the counterfeits is 89 per cent - however, just under eleven per cent of the originals would also test positive (see graph below).

All blue dots below the threshold drawn in green are original van Gogh paintings that would be classified as "conspicuous" by the model. The red dots below the line represent detected forgeries. The somewhat obscured red dot at the probability value of 0.81 represents the "Mill of Wijk", the dot above it and even more obscured at 0.87 denotes the only one of eight forgeries by the art collector Otto Wacker that was not recognised as such.

The Wacker forgeries were made available to Alexander Thamm by Henry Keazor, Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Heidelberg. They are reproduced below.

Paintings by the art dealer Otto Wacker recognised as forgeries:

Painting by the art dealer Otto Wacker not recognised as a forgery:

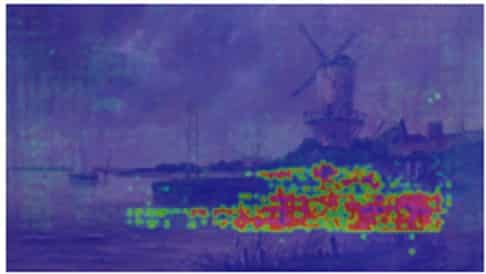

"Mill of Wijk" and Class Activation Map of the image:

The brightly marked areas show parts of the picture that so-called convolutional neural networks have identified as distinctly "van Gogh typical". However, this is to be seen as an ex-post observation, i.e. as a retrospective analysis of the model's mode of operation: the algorithm receives as input from each work of art only 100 randomly selected and unchanged image sections, each measuring 224 x 224 pixels. The algorithm itself learns during training which areas or parts of the picture are "characteristic" for a painter or not.

Neither Alexander Thamm GmbH nor Wolfgang Reuter have any contact or connection with the current owner of the painting, the auction house or anyone else involved in the planned auction. The analysis was carried out on their own initiative and out of purely scientific and without any commercial interest.

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us by phone (+49 151/ 14659820) or by e-mail (wolfgang.reuter@alexanderthamm.com) to Wolfang Reuter.

Learn more about how the algorithm works in our Whitepaper "Image Recognition with AI

0 Kommentare