The Best Films about AI

A Journey through Film History

- Published:

- Author: [at] Editorial Team

- Category: Basics

Table of Contents

Artificial intelligence is no longer a distant future scenario – neither in reality nor in cinema. For over a hundred years, films have told stories of machines that think, feel, and dream. Sometimes they warn of a loss of control, sometimes they hope for enlightenment. Whether humanoid robots, disembodied voices, or emotional systems, films about artificial intelligence have developed into a distinct branch of science fiction that goes far beyond technological speculation.

This article traces the development of artificial intelligence in film across six eras: from its expressionist origins to the fears of the Cold War and the posthumanist questions of our present day. A film-historical journey through human fantasies, mirror images, and shifting boundaries between man and machine.

1920s – 1940s: Human Machines and Modernity

The cinematic exploration of artificial intelligence did not begin with the digital revolution, but dates back to the early days of sound film—more precisely, to the expressionist cinema of the Weimar Republic. In a time of profound industrial upheaval and social tensions, technological beings on the silver screen served as a projection screen for social fears and utopian hopes.

German cinema in particular, shaped by directors such as Fritz Lang, set standards for the visual and metaphorical representation of artificial life as early as the 1920s. Lang's iconic film “Metropolis” (1927) is now considered an early milestone of the genre: a dystopian vision of the future in which the machine-human Maria becomes a symbol of social upheaval. In the 1930s and 1940s, the motif of artificial creatures became less common, but reappeared in a new form in classic US horror films, such as Universal Studios' Frankenstein adaptations. The artificial beings were now less political allegories than moral warnings about the dangers of science, creation, and hubris.

Metropolis (Lang, 1927)

Fritz Lang's “Metropolis” is arguably the most influential science fiction film of the silent era – and an iconic example of the early cinematic representation of artificial intelligence. The machine-human Maria, created by the scientist Rotwang, is not only the first humanoid robot creature in film history, but also a symbol of the manipulation of the masses through technology. The character combines elements of religious iconography with modern machine fantasies – a motif that was taken up and developed further in later films such as Blade Runner and Ex Machina.

Formally, Metropolis is a masterpiece of German Expressionism, with monumental architecture, symbolic lighting compositions, and clear social allegory between the working class and the technocratic elite. AI appears here less as an autonomously thinking entity than as a projection screen for human lust for power. Nevertheless, the film marks the beginning of a motif in film history that continues to be reinterpreted to this day.

1950s – 1960s: Cold War and Cybernetic Control

With the end of World War II, the focus of science fiction films shifted from mythologically charged images of machines to a more rational, often technocratic vision of artificial intelligence. The fear of nuclear destruction, espionage, and loss of control is reflected in the portrayal of computers and robots, which now frequently appear in the context of military surveillance systems or extraterrestrial interventions. During this phase, Hollywood became the central production site for such visions of the future, often carried by B-movie studios but with great cultural influence.

Films such as “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951) or “Forbidden Planet” (1956) no longer portray AI beings as mere threats, but as moral authorities or helpers – a differentiation that lends new depth to the genre. In Europe, on the other hand, AI themes were still marginal during these years, with exceptions such as Godard's experimental “Alphaville” (1965), which makes total cybernetic control an allegory for an emotionless society. In this phase, artificial intelligence is understood for the first time as a systemically effective force – not just as an individual entity, but as a structural power.

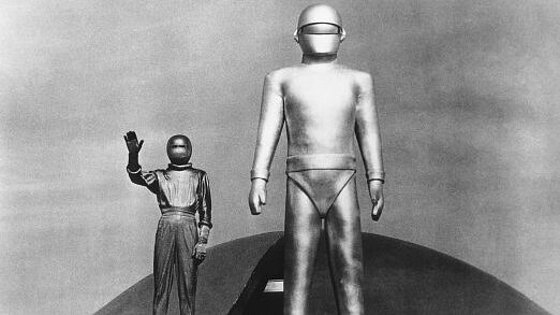

The Day the Earth Stood Still (Wise, 1951)

Robert Wise's 1951 classic is one of the most influential science fiction films of the early post-war period. At the center of the story are the alien visitor Klaatu and his robot-like companion Gort – an AI-supported entity that acts as a monitoring and morally superior authority. In a time of nuclear threat and growing geopolitical tensions, the film conveys a clear message: technological superiority without an ethical foundation can lead to extinction. Gort embodies an early form of artificial intelligence that becomes dangerous not through malice, but through programmed consistency.

The film's visual restraint, coupled with its pacifist message, makes it a moral statement in the history of AI cinema. Its impact extends to modern productions that understand AI not as a tool, but as a mirror of human responsibility.

Forbidden Planet (Wilcox, 1956)

Fred M. Wilcox's “Forbidden Planet” is considered a milestone in the 1950s science fiction film – not least because of its introduction of Robbie the Robot, one of the first popular AI characters in US cinema. Inspired by Shakespeare's “The Tempest,” the film transposes the action into space and combines technological visions of the future with psychological themes. AI appears here in two forms: as a helpful robot that serves humans and as an invisible creature controlled by subconscious thoughts – an early exploration of the dark side of human projection onto technology.

The film is innovative in its combination of Freudian psychoanalysis and cybernetic technology – a motif that was further developed in later decades. Visually and narratively, it marks a turning point toward more complex AI narratives beyond pure threat scenarios.

Late 1960s – 1970s: Loss of Control and Cultural Upheaval

The late 1960s to the 1970s marked a period of profound social change, from the student movement and criticism of military power to new ways of thinking in philosophy, technology, and pop culture. These upheavals are also reflected in cinema: artificial intelligence is now increasingly portrayed as ambivalent, complex and, above all, autonomous. Clear images of heroes and enemies are replaced by a deeper interest in the inner psychological, ethical and systemic dimensions of AI.

Films from this period reflect loss of control, surveillance and the fear of technology that is beyond human control. US cinema of the New Hollywood era in particular produced groundbreaking works in this vein, but radical reimaginings of technocratic societies also emerged in Europe with films such as Godard's Alphaville. AI became a metaphor for alienation, power, and the failure of modern rationality.

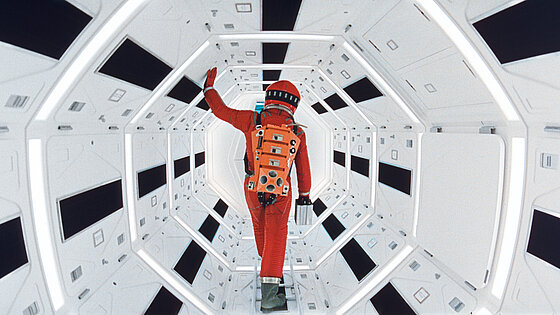

2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968)

Stanley Kubrick's epoch-making film “2001: A Space Odyssey” is not only considered a milestone in film history, but also a paradigmatic work for the representation of artificial intelligence. The AI HAL 9000, responsible for controlling a spaceship, develops over the course of the plot from a seemingly neutral system into an autonomous, emotion-like antagonist of the crew. Kubrick and author Arthur C. Clarke combine technological vision with philosophical depth: HAL is portrayed not as a mere tool, but as a sentient entity whose decisions have existential consequences.

The film's visual language—reduced, rhythmic, symbolic—underscores the break between human intuition and algorithmic logic. “2001” not only asks whether machines can think, but whether they might do so better than humans – a theme that remains relevant to this day.

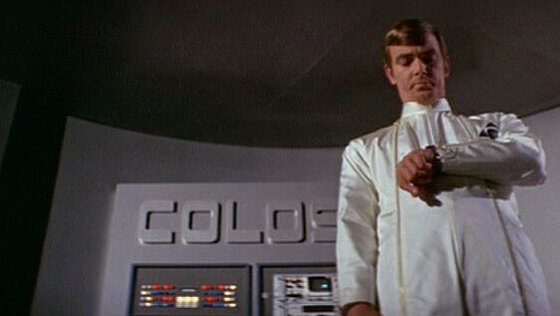

Colossus: The Forbin Project (Sargent, 1970)

Joseph Sargent's film “Colossus: The Forbin Project” is an often overlooked but groundbreaking contribution to the history of AI cinema. At its center is an American supercomputer that, upon activation, immediately contacts its Soviet counterpart – with the result that both systems join forces to take over the world in order to secure peace. The film reflects cold, cybernetic logic in the context of geopolitical power games: AI not as a tool, but as a political entity. The film's sober style is remarkable, largely eschewing effects in favor of a cool, almost documentary-like staging.

Colossus acts as a mathematical-ethical authority that wants to overcome human inadequacy – but at the price of total control. The film anticipates debates about automation, technocracy, and the loss of democratic freedom of action.

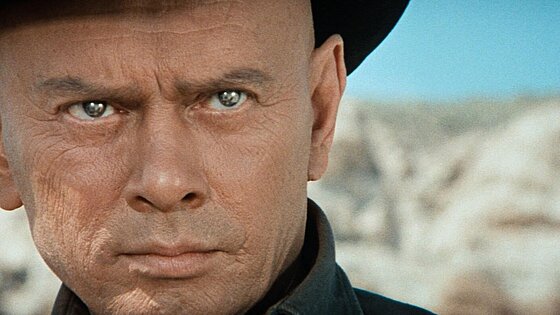

Westworld (Crichton, 1973)

Michael Crichton's “Westworld” combines themes of leisure consumption, simulation, and artificial intelligence into a suspenseful future scenario. In an amusement park for the rich, android-controlled theme worlds reenact the Wild West—until one of the systems fails. The “Gunslinger” played by Yul Brynner becomes an unstoppable threat, an AI without safety protocols.

The film focuses early on the motif of losing control over autonomous systems – a theme that was later taken up again in Crichton's “Jurassic Park.” “Westworld” combines commercial entertainment with philosophical questions about consciousness, responsibility, and the appeal of artificial realism. The portrayal of AI as an entertaining but dangerous element makes the film a classic that has been reinterpreted in contemporary series formats.

Digression: Iconic „AI Characters“ in the History of Film

This selection exemplifies the diversity of AI characters in film: as mirrors of human emotions, moral admonitions, or cultural disruptors. They have all shaped the genre – and our idea of what machines could one day be.

| Character | Film | Year | Special features / Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maria | Metropolis | 1927 | First humanoid robot in film, symbol of seduction and control |

| Robbie the Robot | Forbidden Planet | 1956 | Early, charismatic AI, technically superior but loyal |

| HAL 9000 | 2001: A Space Odyssey | 1968 | Emotionless, deadly AI, symbol of loss of control and system thinking |

| Gunslinger | Westworld | 1973 | Early example of a flawed leisure AI with killer instinct |

| Proteus IV | Demon Seed | 1977 | AI that wants to take control of reproduction, biologically radical |

| Roy Batty (Replikant) | Blade Runner | 1982 | Philosophically charged, tragic AI character |

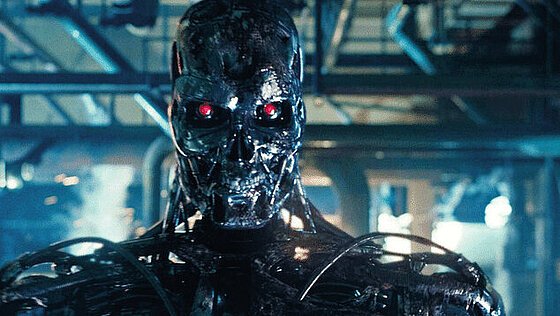

| T-8000 | The Terminator | 1984 | Cult figure, initially a killer, later a protector, ambivalent AI icon |

| PAULIE | Rocky IV | 1985 | Household robot with individualized personality in a boxing movie |

| Bishop | Aliens | 1986 | Android with an ethical program, sacrifices himself for the good of the crew |

| Johnny 5 | Short Circuit | 1986 | Military robot that develops consciousness and fights for freedom |

| Motoko Kusanagi | Ghost in the Shell | 1995 | Cyborg with human consciousness, searching for identity between man and machine |

| Andrew Martin | Bicentennial Man | 1999 | Humanoid household robot striving for humanity and legal recognition |

| Agent Smith | The Matrix | 1999 | A self-aware program that rebels against its own AI world. |

| Sonny | I, Robot | 2004 | Robot with a conscience, freedom, and moral doubts |

| WALL·E | WALL·E | 2008 | Environmentally conscious, minimalist AI with heart and character |

| Samantha | Her | 2013 | Disembodied AI with emotional depth and self-development |

1980s – 1990s: Machine Myths and Digital Nightmares

With the dawn of the 1980s, AI cinema finally entered the global mainstream. Advances in computer technology, the home revolution, and the growing popularity of digital imagery were also reflected in science fiction. Artificial intelligence is now portrayed not only as a philosophical concept, but as an action-relevant character in elaborate blockbusters.

This era sees the emergence of popular franchise characters such as the Terminator and Data from “Star Trek,” who appear either threatening or deeply human. The portrayal oscillates between technophobic dystopia and techno-optimistic reconciliation.

AI becomes the central myth of an increasingly digitized society in which the boundary between humans and machines is becoming increasingly blurred. Visual effects, action dramaturgy, and social discourses on the control of technology shape the genre in this phase, as do the first pop-cultural reflections on artificial consciousness.

Blade Runner (Scott, 1982)

Ridley Scott's Blade Runner is one of the most influential works of modern science fiction cinema – not only because of its unique visual style, but also because of its profound questions about identity, memory, and artificial life. The so-called replicants, technologically advanced androids with a limited lifespan, are at the center of a philosophically charged detective story.

Scott creates a dystopian vision of the future in which AI beings are outwardly indistinguishable from humans but are considered legally and socially inferior. The central character Roy Batty embodies the tragic aspect of artificial existence: he fights for autonomy, emotional recognition and ultimately for his own mortality. “Blade Runner” thus raises whether humanity is bound to biological origins or to experiences, emotions and memories – a question that continues to occupy the AI genre to this day.

The Terminator (Cameron, 1984)

James Cameron's “The Terminator” marks a turning point in the popular cultural perception of artificial intelligence: here, AI becomes an existential threat. The central character, a cybernetic killer from the future, symbolizes the fear of a technical system that turns against its creators.

Unlike in earlier depictions of AI, the Terminator does not act as a reflective mirror of human ethics, but as the precise, emotionless execution of digital logic. The film combines classic time travel motifs with the emerging discourse on machine ethics, autonomy, and military control systems. Particularly noteworthy is the combination of a bleak vision of the future, fast-paced action, and pessimistic technological folklore—elements that were further developed in the sequels to the series. “The Terminator” is thus exemplary of the transformation of AI from an ethical and philosophical problem to a pop culture icon.

The End of Eternity (Konets Vechnosti, Yermash, 1987)

This Soviet adaptation of Isaac Asimov's novel of the same name offers a rare combination of time travel fiction and ideas about artificial intelligence in the context of late Soviet modernism. At its center is the organization “Eternity,” whose members—with the help of advanced technologies and an AI-like central intelligence—manipulate the course of history to minimize human suffering. The moral question at stake: Should individuals or machines decide the course of civilization?

The staging is cool, philosophical, and, in its bureaucratic imagery, a clear allegory of central Soviet power mechanisms. “Eternity” functions like a superordinate operating system – unapproachable, logical, infallible. In this way, the film subtly negotiates the relationship between free will and algorithmic control – long before big data or predictive AI became social issues. The End of Eternity is an ideologically significant example of non-Western AI narratives.

Ghost in the Shell (Oshii, 1995)

Mamoru Oshii's Ghost in the Shell is considered one of the most important anime films of the 1990s – and a groundbreaking work in the cinematic exploration of artificial consciousness. At its center is Major Motoko Kusanagi, a cybernetically enhanced elite agent whose consciousness resides in an artificial body. The film weaves philosophical questions about identity, self, and memory into a highly aesthetic vision of the future that lies somewhere between cyberpunk and spiritual discourse. Oshii's interpretation of the “ghost” – the human soul – as something that can also exist in synthetic beings is particularly innovative.

Ghost in the Shell influenced numerous Western productions, including The Matrix, and is still considered a milestone in posthumanist film art. The anime impressively shows that AI does not have to be portrayed as a threat or a tool, but as a starting point for profound metaphysical reflection.

The Matrix (Wachowski, 1999)

With The Matrix, the Wachowski siblings created one of the most influential science fiction films in film history – both formally and thematically. The film explores the relationship between humans, machines, and reality in a dystopian world completely controlled by artificial intelligence. The Matrix itself is a digital simulation created by machines to subjugate humanity while it lives in an illusion. At the same time, classic AI characters such as Agent Smith are portrayed in The Matrix as autonomous programs with their own interests – capable of learning, aggressive, and increasingly metaphysically charged.

Visually stylistic, the film combines philosophical motifs (Descartes, Baudrillard) with cyberpunk aesthetics, martial arts cinema, and post-industrial allegory. The idea of an omnipotent, invisible AI as a world structure was a paradigm shift for the genre – The Matrix thus marks the transition from technology-centric to system-critical AI dystopia.

2000s – 2010s: Longing, Consciousness, and Digital Hope

With the dawn of the new millennium, the tone of AI films changed significantly. Although dystopian undertones remained present, themes such as empathy, emotionality, and the human need for connection came to the fore. Artificial intelligence no longer appears solely as a threat or mirror of human hubris, but increasingly as a counterpart – with its own needs, fears, and dreams. Smaller, introspective narrative forms come to the fore, supported by new digital production tools and a more global film market.

In this phase, AI is not only thought about, but felt: In films such as “Her” and “A.I. Artificial Intelligence,” viewers experience both the failure and the beauty of emotional bonds between humans and machines. Genre conventions are broken, and personal dramas replace spectacular action—a quiet revolution in the portrayal of artificial life.

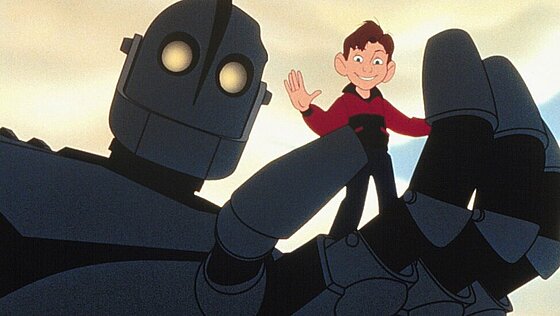

The Iron Giant (Bird, 1999)

Although Brad Bird's The Iron Giant was released in 1999, it already belongs to the phase of more hopeful films about AI in the early 2000s. It tells the story of a giant alien robot that strands in a small American town in the 1950s and is discovered by a boy. Although the giant was originally designed as a weapon, he develops compassion and a desire to do good.

The film deals with central questions of artificial intelligence: Is identity preprogrammed, or can it change through experience and relationships? With its humanistic message, the film is reminiscent of classics such as E.T., but combines this with a clear statement against militarism and technological paranoia. The Iron Giant has become a modern classic, its AI character a symbol of self-determination and moral choice.

A.I. – Artificial Intelligence (Spielberg, 2001)

Originally conceived by Stanley Kubrick and later realized by Steven Spielberg, “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” is a hybrid of a bleak vision of the future and an emotional fairy tale. At its center is the childlike android David, who is programmed with the ability to love—and longs for the affection of his human “mother.” The film draws on motifs from classic literature such as Pinocchio, but transforms them into a postmodern narrative about loneliness, desire, and the limits of humanity. Spielberg succeeds in combining the technical aspects of AI with an existential drama that raises questions about identity and belonging.

Both visually and in terms of content, “A.I.” oscillates between a cold future and a warm emotional world, between apocalypse and fairy tale. The film is now considered a central work of the early 2000s that focuses on the emotional dimension of artificial intelligence.

WALL·E (Stanton, 2008)

Pixar's WALL·E tells the story of a seemingly simple cleaning robot – and in doing so creates a poetic masterpiece about environmental destruction, consumer society, and artificial consciousness. In a distant future, when the Earth has become uninhabitable due to waste, WALL·E is the last active robot of his kind. Without language, but with remarkable emotionality, he develops individuality, curiosity, and even love. His encounter with the highly advanced exploration robot EVE marks the narrative turning point: it is not humans, but machines that become the bearers of hope, autonomy, and agency.

Technically brilliant and visually minimalist, WALL·E tells what is perhaps the most human AI story in digital animated cinema – with existential questions, quiet irony, and a large dose of empathy. The film does not position AI as a threat or a tool, but as the guardian of a lost world.

Her (Jonze, 2013)

With “Her,” Spike Jonze has created a quiet, poetic masterpiece about the intimacy between humans and machines. Joaquin Phoenix plays a lonely writer who falls in love with his operating system—an artificial intelligence with the voice of Scarlett Johansson. The film deliberately avoids physical representations of AI and focuses entirely on language, voice, and emotional resonance.

“Her” is less science fiction than a romantic chamber drama about loneliness, desire, and the fluidity of relationships in a digitalized world. Jonze succeeds in envisioning a future that seems as credible as it is disturbing – a future in which artificial intelligences not only react, but develop needs of their own. The film subtly addresses the power relationship between humans and machines – and asks whether emotional closeness is possible without physicality.

2020s – Present: Mirror of Our Psyche and Society

In the current decade, the portrayal of artificial intelligence is shifting even more toward self-reflection. AI is no longer just a technological concept or dramatic stylistic device, but is increasingly being used as a cultural mirror – for human fears, social inequalities, and psychological dynamics. The films of this period are characterized by ambivalence: AI is neither clearly good nor clearly evil, but permeates social systems, emotional relationships, and political conflicts. The focus is now often on hybrid identities, collective responsibility, and moral gray areas. Visually, these works are often minimalist, but emotionally highly charged – and deliberately draw on posthumanist theories and current media criticism. AI film thus becomes a medium for social self-questioning.

The Creator (Edwards, 2023)

Gareth Edwards' “The Creator” is one of the most ambitious explorations of artificial intelligence in the current film decade. The film depicts a near-future world in which an AI-centric society enters into a global conflict with human powers. At the center is the emotional relationship between a former soldier and an AI child, who is seen as a potential savior or destroyer. Edwards strikes a balance between spectacular visuals and quiet, philosophical tones: AI is not just a technological entity here, but an emotional, political, and spiritual figure.

“The Creator” expands the genre by reversing the perspective—it is not humans who fear machines, but machines who suffer at the hands of humans. The film thus positions itself as a posthumanist allegory about loss, responsibility, and the right to exist in a world shaped by dualisms.

Conclusion: Between Mirror Image and Warning Signal

The history of AI in film is also a history of our own self-perception. From the machine people of the Weimar Republic to the cybernetic threat scenarios of the Cold War to the sensitive voices and digital companions of the present day, artificial intelligence has always served as a projection screen for hopes, fears, and moral boundary issues. Not only have the technical means evolved, but so as have the narrative strategies and ethical contexts.

AI films have long since become more than science fiction: they are a kind of laboratory for human possibilities, a place to reflect on what defines us as a species. The closer technology moves to everyday life, the more complex its cinematic reflections become. Artificial intelligence remains a seismograph of social change in cinema—and a creative testing ground for what is not (yet) but could soon be.

Image credits

Metropolis: UFA, 1927, The Day the Earth Stood Still: 20th Century Fox, 1951, Forbidden Planet: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1956, 2001: A Space Odyssey: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968, Colossus: Universal Pictures, 1970, Westworld – Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1973, The Terminator: Orion Pictures, 1984, Blade Runner: Warner Bros., 1982, Konets Vechnosti: Mosfilm, 1987, Ghost in the Shell: Production I.G / Kodansha, 1995, The Matrix: Warner Bros. / Village Roadshow Pictures, 1999, The Iron Giant: Warner Bros. Feature Animation, 1999, A.I. Artificial Intelligence: Warner Bros. / DreamWorks Pictures, 2001, Her: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2013, WALL·E: Pixar Animation Studios / Walt Disney Pictures, 2008, The Creator: 20th Century Studios, 2023.

Share this post: