The legal disputes regarding copyrights in the training of Image- or art-generating algorithms has not yet been decided. But regardless of the outcome of the proceedings, the development will scrutinise and redefine the position of artists.

Above all, however, it will call into question the reception of art characterised by the Enlightenment. Up to now, this has focussed, possibly wrongly, on the artist as an individual.

Are we witnessing the beginning of the end of the cult of personality in art?

Mechanical art becomes a museum. When the most famous work in the Mauritshuis in The Hague, Johannes Vermeer's "Girl with a Pearl Earring", was loaned to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for three months at the beginning of 2023 along with around a dozen other paintings by the Baroque artist, the museum filled the prominent vacancy with an imitation. The special thing about it: it was not an artist who created the interpretation of the original - but the algorithm "AI Midjourney". Julian van Dieken used artificial intelligence to create his version, called "Girl with Glowing Earrings" (see Figure 1), which he then reworked using Photoshop [1].

The Mauritshuis organised a competition during the absence of its most famous Van Vermeer. The public was invited to create "their own girl", inspired by the Vermeer painting, to hang in its place. A jury then decided on the total of 3482 entries.

This was followed by a public outcry. Artist Iris Compiet found the amount of AI images submitted "incredibly offensive" [2]. The Mauritshuis responded with a statement from a spokesperson saying: "We knew that [van] Dieken's work was created with artificial intelligence, but we liked his image and that was enough for us." And further: "Basically, the only criterion was that the work was based on a creative process."[2]

The succinct and probably naive justification infuriated other artists. According to Eva Toorenent, artist and Dutch advisor to the organisation European Guild for Artificial Intelligence Regulation (EGAIR), the museum "did not understand the technology". The museum's "uninformed response to the criticism was the most disappointing thing", Toorenent said. "I explained in a detailed email why AI-generated art in its current form is highly unethical and has no place being highlighted and celebrated in a museum." In response, she received "a copy-paste reply in which they reiterated their decision".[2]

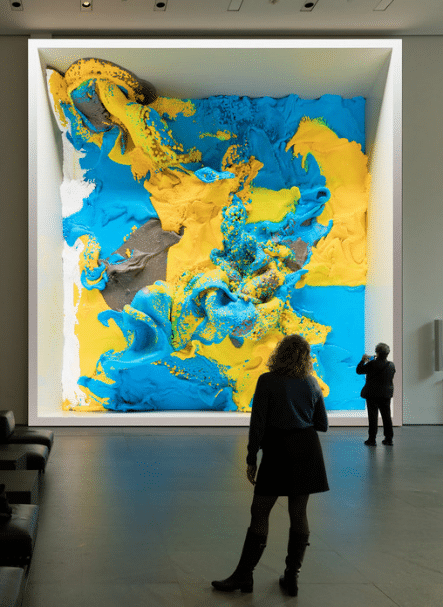

At the same time, the Museum of Modern Art in New York dedicated the exhibition "Unsupervised" to Refik Anadol. The artist's installation "ponders what a machine might dream of after seeing more than 200 years of art in MoMA's collection", according to the museum's website [3]. A section of the installation can be seen in Figure 2.

Here, too, there was a hail of criticism. For example, from Jerry Saltz, a renowned New York art critic. For him, Unsupervised is "crowd-pleasing mediocrity". The installation merely utilises "existing written, photographic and artistic material". In his eyes, MoMA's foray into AI fails "exactly where other AI programmes have failed." He continues: "If AI is to create meaningful art, it needs to bring its own vision and vocabulary, its own sense of space, colour and form. Things that Unsupervised lacks." [4]

Saltz is right. Ultimately, this is art from the AI can. The generative AI modelsThe artists who supposedly create independent works of art draw on hundreds of millions of pictures and thus (also) on the artistic heritage of many generations.

And they are becoming ever more popular, the market ever larger. In addition to the established services AI Midjourney, Supermachine, Dream Studio, Artsmart, Neuroflash, Nightcafe and many others, over 100 new providers entered the market this year [5]. And the established software companies are also responding to the trend. Microsoft, for example, has integrated an image generator into its Bing search engine [6].

It is questionable whether these applications are even legal. In any case, copyright issues play a decisive role. Ultimately, courts will decide on the permissibility of these algorithms. The first lawsuits have already been initiated.

On 13 January 2023, illustrators Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan and Karla Ortiz filed a class action lawsuit against Midjourney, DeviantArt and Stability A.I. in the Northern District of California. DeviantArt is behind the image generator DreamUp and Stability A.I. has launched the algorithm Stable Diffusion. They describe these text-to-image platforms as "collage tools ... that infringe the rights of millions of artists" [7].

"Defendants are using copies of the Training Images," the complaint states, "to generate digital images ... that are derived solely from the Training Images and add nothing new," but "have a substantial negative impact on the market for Plaintiffs' work...." Anderson, McKernan and Ortiz also criticise the fact that AI generators have made it possible to generate artworks "in the style" of certain artists and thus "siphon off commissions from the artists themselves" [7].

A few weeks later, on 2 March 2023, the stock photo provider Getty Images also sued Stability A.I. The image database accuses the company of misusing more than 12 million Getty photos to train its Stable Diffusion AI image generation system. [8]

Basically, these and other similar processes are about the question of when copying stops and independent art is created through changes and new compositions of works. And secondly, whether machines have the same rights as humans.

The latter was raised by renowned AI expert and researcher Andrew Ng. Ng was a professor at Stanford University and co-founder and co-director of Google Brain before founding the online platform Coursera together with Daphne Koller. He is also the founder of the AI companies Landing AI and deeplearning.ai.

In his newsletter "The Batch" of 8 February 2023, he wrote in response to the Getty Images lawsuit announcement: "The last time I visited the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California, I saw budding artists sitting on the floor copying masterpieces on their own canvases. Copying the masters is an accepted part of becoming an artist.

By copying many paintings, the pupils develop their own style. Artists also regularly look at other works for inspiration. Even the masters whose works are studied today have learnt from their predecessors. Would it be fair for an AI system to learn in a similar way from paintings created by humans?" [9]

Ng published a photo showing artists copying the painting "The Dancing Lesson" by Edgar Degas. It can be seen in Figure 3.

These questions will not only occupy the courts, but will also characterise public discussion and perception in the near future. And this is by no means just about the issue of equal opportunities between humans and machines. The copyright issues surrounding AI-generated images call into question the basis of our reception of art, which has changed dramatically since the Enlightenment.

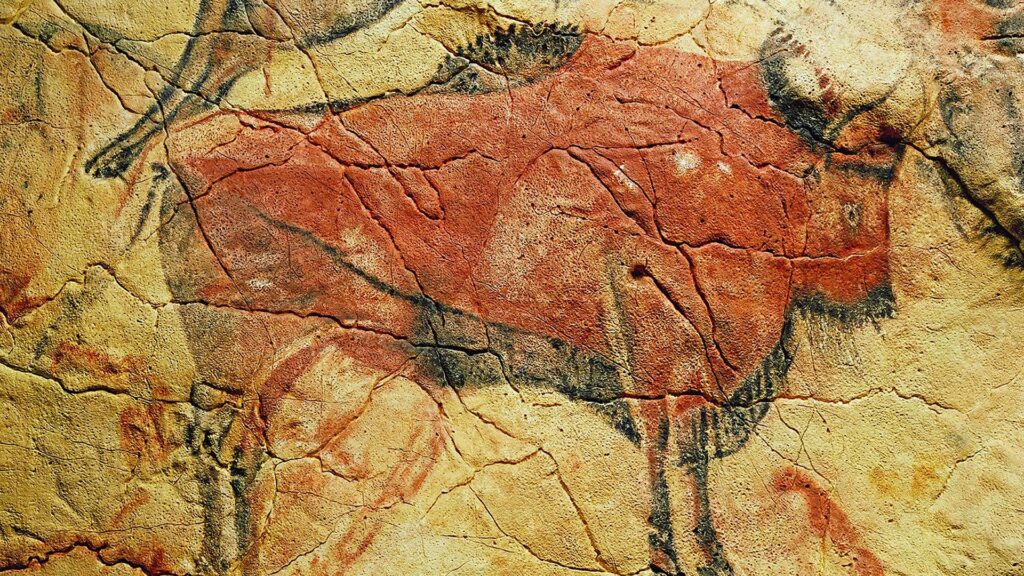

Until the early modern period, art was primarily one thing: anonymous. The creators of early works, regardless of the form of expression, are usually not recorded. Who made the cave drawings from the Stone Age, see Figure 4? Who chiselled the world-famous "Nike of Samotrakhe" shown in Figure 5? Who wrote the Bible?

Figure 5: "Nike of Samotrakhe", front view (left), three-quarter view (centre) and side view (right), ca. 190 BC, Louvre, Paris.

Okay, you might say, "fair point" as far as the Bible is concerned. But Homer wrote the Illiad and the Odyssey. Yes, he did. But as a chronicler. The first oral versions were probably written in late Mycenaean times. They were disseminated over centuries by singers and probably also altered. And even the Middle Ages did not recognise the profession of artist.

One could argue that the names of these artists may have been forgotten over the centuries. But this inevitably raises the question of why they have been forgotten. After all, we know almost everything about the rulers of the Roman Empire and a great deal about those of the Hellenistic and Babylonian empires, as well as those of ancient Egypt. We know their names, as well as those of the popes and earlier religious dignitaries. Even economic figures, i.e. merchants, as well as lawyers, fraudsters, prostitutes and ordinary citizens have been passed down to us by name from very early epochs. The only thing we don't know is who the artists were.

There may be a few exceptions, but art was much more than that before the Enlightenment. It was the creative expression of a collective and not of an individual.

This changed dramatically with the Enlightenment. In 1641, René Descartes formulated one of the most influential sentences in human history: "Cogito, ergo sum" - or in German: "I think, therefore I am". This sentence shaped the Enlightenment and individualism, and thus the world view that is still valid today, at least in the West: it was the realisation of our consciousness formulated with these five words that in turn strengthened the position of the individual, granted them rights and also placed artists, as individual creators, above the diverse forms of expression of a society consisting of nameless individuals. It was the beginning of a cult of personality, the likes of which had never been seen before in art.

Rembrandt was already a kind of painting rock star in Amsterdam in the mid-17th century. And he still is today. Lovers are happy to pay more than 100 million euros for his works. But woe betide them if one of his paintings is written off by some art-historical opinion leaders. Then the same work of art is worth just a few hundred thousand euros. But why actually? After all, the painting is completely unchanged.

Basically, this is the expression of a completely exaggerated cult of personality in art, which seems all the more absurd when one realises that some paintings from the Rembrandt school have been attributed to eight different artists by the respective top Rembrandt experts in the past - and the authorship of numerous works is still disputed today [10]. Or when you realise how many forgeries have found their way into certain catalogues raisonnés, such as those of Heinrich Campendonk, Alexej von Jawlensky or Max Ernst, to name just a few.

For art historian Bernd Lindemann, former director of the Gemäldegalerie Berlin, the authorship of a work of art plays a subordinate role at best. "A work of art is a work of art," he says, "regardless of who created it. The name of the creator merely has a mercantilist meaning" [11].

But the issue raised by the copyright dispute goes much deeper.

It is not just a question of whether art exists or can exist independently without the context of the artist as an individual (but in the context of the political and social conditions at the time of its creation).

It is also about the question: how much Rembrandt is actually in a painting by Rembrandt, and how much Monet is in a painting by Monet.

The generative AI models that create independent works - let's leave aside the question of whether this is art - draw on the creativity of both well-known and long-forgotten painters. They plagiarise their styles and mix them freely and uninhibitedly.

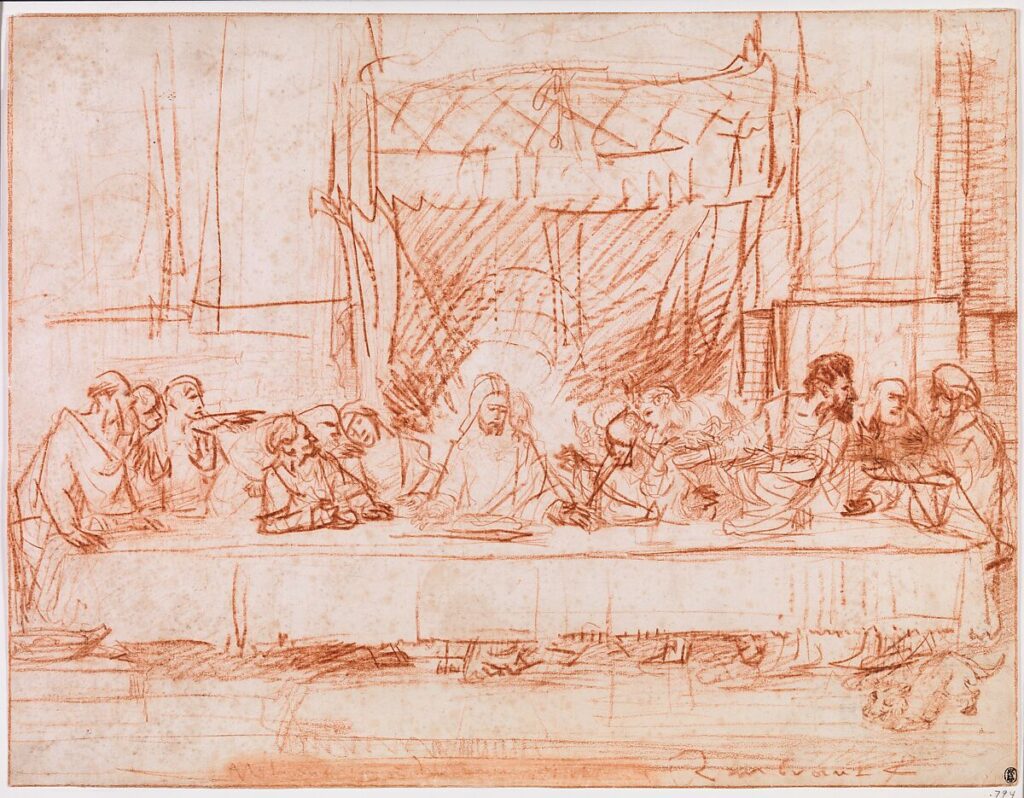

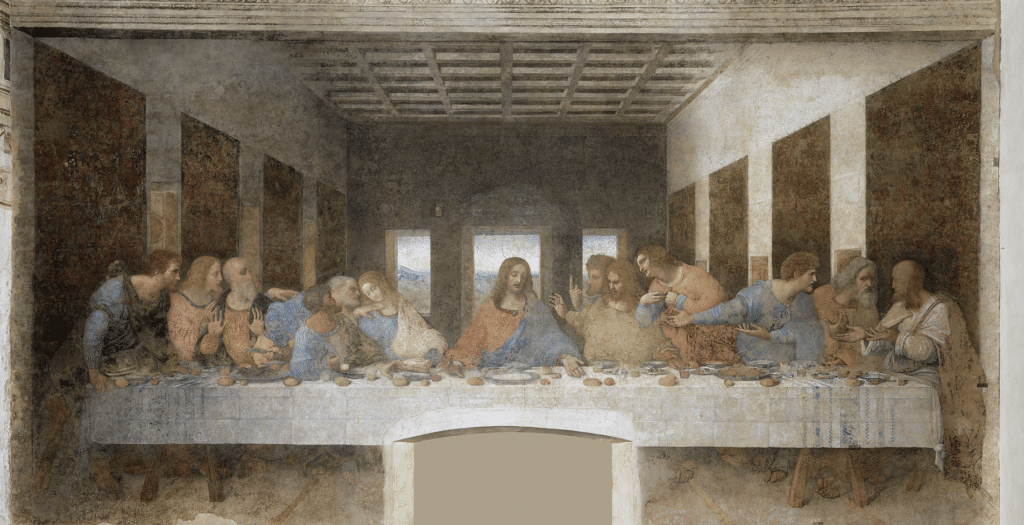

As did the artists. Raphael studied and drew Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" in his studio (Figure 6). Rembrandt studied Raphael's Last Supper - and copied it (Figure 7). Eduard Manet reinterpreted Rembrandt's "Anatomy of Dr Tulp" - and was strongly influenced by Diego Velasquez's style (Figure 8).

Figure 6: Raphael Sanzio's sketch of the Mona Lisa, which he drew in Leonardo da Vinci's workshop around 1504, Louvre, Paris (left). The original painting, probably altered by da Vinci in the course of his life, Louvre, Paris.

Figure 7: Rembrandt's sketch of the Last Supper by Raphael, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (above), original painting by the Italian Renaissance artist, Dominican monastery of St Maria delle Grazie, Milan, (below).

Figure 8: Edouard Manet's interpretation of Rembrandt's painting "The Anatomy of Dr Tulp", private collection, location unknown (left), original painting by Rembrandt, Mauritshuis, The Hague (right).

And there are countless other examples. Would Caravaggio even be conceivable without Da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo? Probably not. And what would Picasso be without Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Juan Gris and Pierre Bonnard?

So is art really as individual as we think? Are works (whether art or other works) not also the product of dozens, hundreds or thousands of other works by other people or artists? How much individuality is there in a work of art - and how much does the artist owe to his or her cultural background? And where, pray tell, is the difference between a machine that makes use of the artistic heritage of the West or even of the whole of humanity - and a person who does the same?

Or to put it another way: is the freedom of the individual and artistic self-determination postulated in the Enlightenment ultimately nothing more than a chimera? A dream that never becomes or can never become reality?

Everyone has to find the answer to this question for themselves. My answer is: No.

No, the (artistic) freedom of the individual is not a utopia. We humans are actually capable of thinking and creating something new - and not just rummaging through the mothballs of past works. To what small extent remains to be seen.

In every stylistic epoch, there are pioneers and artists who, like Claude Monet, for example, shaped Impressionism. But it was never - or rarely - individuals. In most cases, it was groups of artists who inspired and copied each other. Which further diminishes the innovation of the individual in developing a new style of painting. Machines and algorithms are not able to do this. At least not yet.

And there were copyists in every stylistic epoch. In other words, artists who placed no value at all on individuality, on their "own style". Christian Willhelm Ernst Dietrich (1712 to 1774), for example, who later changed his name to Dietricy, limited himself to copying well-known Dutch painters, including Rembrandt. In most cases, he merely imitated the style, but not the motif. The same applies to Tom Keating. The British artist and restorer became known above all for his Edgar Degas imitations. Keating is often labelled a forger - however, he never signed the works of other artists that he imitated stylistically as such, which is why he was never convicted.

Han van Meegeren, whose works are also considered art today - and whose paintings have been shown in numerous exhibitions and retrospectives, is different. The Dutch forger (1889 - 1947) was initially somewhat successful as a painter, but later his works were labelled as "kitsch" and art experts accused him of not being capable of independent creative achievement. As a result, van Meegeren produced numerous forgeries of Dutch masters, including half a dozen in the style of Jan Vermeer. His imitations were so good that even renowned art historians, such as Abraham Bredius, the director of the Mauritshuis at the time, fell for them [12].

But if the works of plagiarists, imitators and even counterfeiters are considered art - why should machine-generated works be treated differently? And what about the other artists, who very much value their own style. Even if this style would be unthinkable without the earlier work of generations of other artists.

Basically, with regard to AI-generated art, the judges not only have to decide whether the use of the works of artists, imitators and counterfeiters in generative models infringes the copyrights of these artists.

In any case, the new technology calls into question the previous social consensus on the performance of individuals and thus the normative justification of the rights of individuals to "their" works.

And the judges may therefore not only have to judge the machines - let's leave aside whether their "output" is art or not - but also whether copyright law in its current form is still up to date in view of technical developments.

List of sources

[1] O.A., "Mauritshuis hangs artwork created by AI in place of loaned-out Vermeer", NL Times, 22.2.2023, accessed online via https://nltimes.nl/2023/02/22/mauritshuis-hangs-artwork-created-ai-place-loaned-vermeer (8.6.2023)

[2] Taylor Michael, "Museum under Fire for Showing AI Version of Vermeer Masterpiece", Hyperallergic, 1 March 2023, accessed via https://hyperallergic.com/805030/mauritshuis-museum-under-fire-for-showing-ai-version-of-vermeer-masterpiece/ (8.6.2023)

[3] Museum of Modern Art, website accessed via https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/821 (8.6.2023)

[4] Jerry Saltz, "MoMA's Glorified Lava Lamp. Anadol's Unsupervised is a crowd-pleasing, like-generating mediocricy", Vulture, 22.2.2023, accessed via https://www.vulture.com/article/jerry-saltz-moma-refik-anadol-unsupervised.html (8.6.2023)

[5] Finn Hillebrandt, "The 14 best image generators in 2023 (free)", accessed via https://www.blogmojo.de/ki-bildgeneratoren/ (9.6.2023)

[6] Patrick Hannemann, "Free image generator in Bing: Microsoft gives you AI tool", Chip, 6 May 2023, accessed via https://www.chip.de/news/Kostenloser-Bildgenerator-in-Bing-Microsoft-schenkt-Ihnen-KI-Tool_184712934.html (9.6.2023)

[7] Min Chen, "Artists and Illustrators are Suing Three A. I. Art Generators for Scraping and 'Collaging' Their Work Without Consent", Artnet News, 24.1.2023, accessed via https://news.artnet.com/art-world/class-action-lawsuit-ai-generators-deviantart-midjourney-stable-diffusion-2246770 (9.3.2023)

[8] Blake Brittain, "Getty Images lawsuit says Stability AI misused photos to train AI", Reuters, 6 February 2023, accessed via https://www.reuters.com/legal/getty-images-lawsuit-says-stability-ai-misused-photos-train-ai-2023-02-06/ (9.3.2023)

[9] Andrew Ng, "The Batch", Newsletter from deeplearning.ai, 8 February 2023 (page 2)

[10] Reuter, Wolfgang: Original or pupil? Possible applications of artificial intelligence in attribution questions using the example of the Rembrandt Research Project. In: Art History. Open Peer Reviewed Journal, 2023 (urn:nbn:de:bvb:355-kuge-600-4)

[11] Personal conversation with Bernd Lindemann as part of an event organised by the Kaiser Friedrich Museumsverein on 5 June 2023 at the Gemäldegalerie Berlin.

[12] Abraham Bredius: An Unpublished Vermeer. In: The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 61, No. 355 (Oct., 1932), Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd, pp. 144-145.

0 Kommentare